- Pivot & Flow

- Posts

- This Guy Became a Billionaire Selling Potato Chips (and then Semiconductor Chips)

This Guy Became a Billionaire Selling Potato Chips (and then Semiconductor Chips)

From the largest seller of french fries to McDonald's to the largest shareholder of $MU

Happy Sunday

Today is on J.R. Simplot, a potato farming billionaire who went on to build what is now the $220B+ semiconductor firm Micron Technology (an all-time business pivot with some lessons for the current AI gold rush). I first heard this story from Trung Phan, an incredible person in his own right.

Lets dig in…

I recently finished Chris Miller's book Chip War, which traces the geopolitical history of the semiconductor industry (and also serves as a reminder that I misallocated my trading during COVID to shorting Carnival Cruise lines instead of Nvidia).

My favorite bit from the book was about J.R. Simplot, an Idaho potato farmer who used his understanding of commodity markets to spot an opportunity in the dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) segment of the semiconductor industry.

And by "an Idaho potato farmer", I mean "the person who became a billionaire supplying McDonald's with 50% of its french fries and used to drive around the city of Boise with a license plate that read SPUD".

Just absolute boss moves.

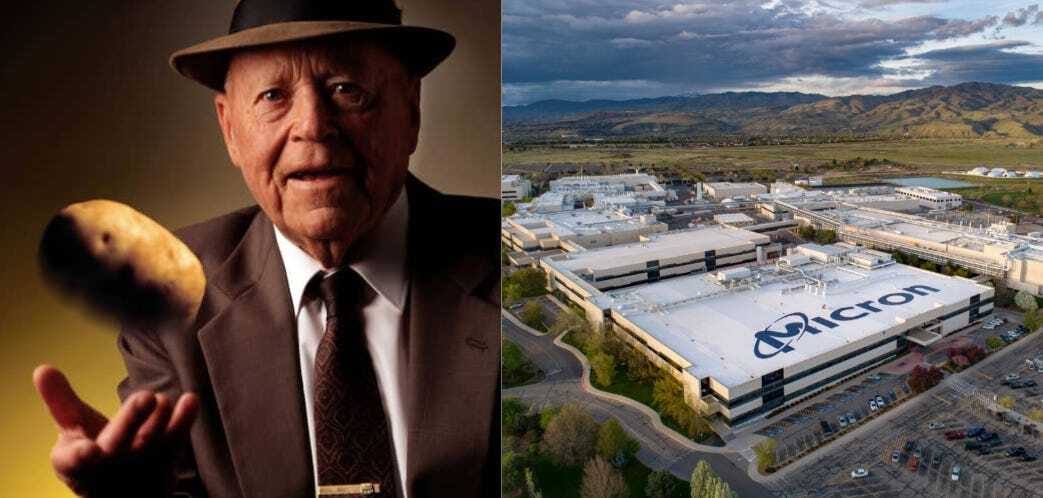

J.R. Simplot (L) and the very very nice-looking Micron HQ in Boise, Idaho (R)

In 1980, he invested $1m into Micron Technology for a 40% stake, which would eventually make him a billionaire again just from memory chips.

Simplot's unlikely career pivot was widely covered in the 1990s with some top-tier headlines:

1992: The Idaho Angel On Their Shoulders (The Washington Post)

1995: The Simplot Saga: How America's French Fry King Made Billions More in Semiconductors (Fortune)

1996: From Mr. Spud to Mr. Chips (The New York Times)

While Simplot passed away in 2008, Micron remains a major semiconductor player with a market cap of $220B+.

Simplot's Potato Empire

John Richard Simplot was born in 1909 in Idaho — America's largest potato exporting state. He'd live for nearly another century, dying in 2008 at age 99.

To understand how unlikely his tech success was: the semiconductor industry's iconic founders were all born much later. Intel's Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore were born in 1927 and 1929. Morris Chang founded TSMC in 1931. Jensen Huang and his glorious collection of Tom Ford leather jackets wasn't born until 1963.

Simplot didn't grow up in a computing revolution, but he was no stranger to cutting-edge technology. It was cutting-edge agricultural technology, as explained by Fortune:

Mr. Simplot got his start in 1923 at the age of 14. After storming out of his father's house in a huff, young Jack set himself up as a hog farmer. His break came during a harsh winter, when feed grain was in short supply, but potato scraps and wild horse meat were plentiful. He adapted the latest boiler technology into a rendering vat that produced a fortified hog slop. The next spring, when his competitors led their scrawny survivors to market, Jack Simplot made a killing with his fat hogs.

Simplot initially funded the business with some insane hustle. His mom gave him $80 when he left the house. He found accommodation at $1 a night, then pulled an incredible arbitrage with local teachers: they were holding interest-bearing paper called "scrip" but some needed cash up front. Simplot offered cash for 50% of the face value, then took out a loan at a bank using that scrip as collateral and bought $600 worth of pigs.

AND ALL AT FOURTEEN YEARS OLD!!

I was making my way through a box set of Goosebumps books at the same age.

That first score put him down the path of not needing a formal education. Simplot never graduated from high school. He just kept commercializing new machines that took potatoes as an input and filled his pockets with filthy fiat as an output. By age 20, he'd made his first million from potato trading and sorting.

In 1929, the stock market crashed and The Great Depression hit. Instead of hurting business, Simplot thrived because he could weather the storm better than competitors.

"I liked hard times," Simplot recalled. "The cream always comes to the top, you know."

He built his potato empire through vertical integration: growing, sorting, shipping, freezing, dehydrating, and feeding culls to cattle. By the mid-20th century, his processing plants could freeze 200 million pounds of potatoes a year and he owned 50% of Idaho's russet potato crop.

Simplot's break-out product was the frozen French fry. Ray Kroc approached him about supplying McDonald's, and Simplot eventually captured 50% of McDonald's French fry business, which grew 30x-40x over two decades. The best part? Simplot sealed the deal with a handshake and never had a written contract with McDonald's.

An absolute boss move.

By the 1970s, Simplot was worth hundreds of millions. But it's his $1 million investment in Micron Technology that gave Boise a lasting economic base beyond agriculture and turned him into a tech billionaire.

Here's how that came to be.

Today’s Sponsor

Like Moneyball for Stocks

The data that actually moves markets:

Congressional Trades: Pelosi up 178% on TEM options

Reddit Sentiment: 3,968% increase in DOOR mentions before 530% in gains

Plus hiring data, web traffic, and employee outlook

While you analyze earnings reports, professionals track alternative data.

What if you had access to all of it?

Every week, AltIndex’s AI model factors millions of alt data points into its stock picks.

We’ve teamed up with them to give our readers free access for a limited time.

The next big winner is already moving.

Past performance does not guarantee future results. Investing involves risk including possible loss of principal.

Micron and the Memory Opportunity

In 1978, twin brothers Ward and Joe Parkinson founded Micron Technology with money from a consulting project building microwave communication systems for local cattle-feed lots. They also raised money locally from dentists and optometrists in Boise.

Once they actually had to make chips, though, these investors realized the upfront costs would be much higher than anticipated. To build a plant that could mass produce DRAM chips, the twins needed millions more. They turned to the Potato King.

That timing couldn't have been better.

Simplot's approach to business deals reflected his deep understanding of commodities. "Hell, we understand cycles," he'd say about markets.

At this moment in 1980, it was a terrible time to be in the DRAM business:

The US had just entered a recession

Intel was pivoting away from memory chips

IBM, Texas Instruments and National Semiconductor all exited the DRAM market

Japanese semiconductor firms controlled 70% of the DRAM business (having benefited from government-backed cheap credit)

DRAM prices were crashing

Every single American venture firm passed on Micron.

One VC said, "Competing with the Japanese in memory was impossible. […] It seemed like throwing your money away."

Not to J.R. Simplot: He'd been through enough harvests to know that the best time to buy a commodity business was when prices were depressed and everyone else was in liquidation.

Simplot received 40% of Micron Technology for $1m. On signing the check, he said, "Boys, it's a gamble, and we're going to take it."

It was less of a gamble than it looked because Simplot was one of the world's foremost experts on the following combination: "commodity market", "prices were depressed" and "everyone else was in liquidation".

He had a playbook.

Winning The DRAM Market

With Simplot's backing, the Parkinson twins built a chip fab in 1981 for ~$10m—10% the typical construction cost—and were selling 64k DRAM chips the next year.

Then Micron went public in 1984 just as the Japanese firms turned the competition dial to 11.

"They dropped the price of DRAMs from $2 to 25 cents and kept it there for 18 months," Simplot said. "They were dumping!"

Intel and 10 other American DRAM makers dropped out, leaving Micron and IBM as the domestic producers (IBM kept chips for internal use).

How did Micron hang around?

They followed Simplot's motto: "the lowest-cost producer of the highest-quality product."

Key factors: Micron had access to cheaper Idaho land and energy compared to Japanese and California competitors. The Parkinson brothers also simplified manufacturing processes—using far fewer production steps than competitors—and modified equipment to handle more wafers per load. Every optimization meant lower prices.

Meanwhile, Japanese firms had less cost discipline because government support kept factories humming regardless of profit.

Micron became one of the loudest voices for US government action against Japanese trade practices. This was personal for Simplot—Japan had tariffs on his potatoes:

"They've got a big tariff on potatoes. We're paying through the nose on potatoes. We can out-tech 'em and we can out produce 'em. We'll beat the hell out of 'em. But they're giving those chips away."

His lobbying helped lead to the U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Trade Agreement in 1986. The Reagan administration placed a 100% tariff on $300m worth of Japanese semiconductors.

This wasn't the first time Simplot played hardball. He'd survived The Great Depression, lived through World War II, and was even booted off the New York Mercantile Exchange in the late 1970s for manipulating Maine potato futures.

The trade agreement proved controversial because lower DRAM supply hurt American electronics manufacturers. These higher prices brought in new competition from South Korea.

But Micron lobbied itself into a 6x sales increase between 1986 and 1988. As a low-cost producer, Micron capitalized on economies of scale to stay in the game along with Samsung and SK Hynix (while nearly every other Japanese and American competitor dropped out).

By the mid-1990s, Simplot remained Micron's largest owner with a ~20% stake and overall net worth of ~$5B.

While Simplot wasn't working day-to-day at Micron—and even had a falling out with the founding Parkinson brothers (who both left)—he was instrumental in decision making. The board met every Monday at 5:45 AM at Elmer's Pancake House in Boise. Get there after six and Simplot would ask, "What's the matter, did you sleep in?" He was also known to steal bacon strips from other board members' plates.

The "did you sleep in" combined with sniping bacon strips is just S-Tier psychological warfare. But for Micron execs, giving up that bacon was worth it because Simplot used experience from building a potato empire to win the DRAM battle: deploying capital, understanding commodity markets, and working the political system.

Micron, China and the Future of AI

Today, Micron Technology is worth $220B+ and is one of Boise's largest employers. It still dominates the DRAM market along with SK Hynix and Samsung (combined 90%+ market share in DRAM and the specialized high-bandwidth memory used in generative AI).

The last major Japanese competitor was Elpida, which Micron acquired in 2013. Taiwan spent billions trying to enter DRAM but couldn't manufacture profitably.

In 2015, Chinese state-backed Tsinghua Unigroup tried to buy Micron for $23B and…c'mon…that wasn't going to happen. This began a decade of Micron becoming a pawn in US-China trade conflict. In 2020, Micron says China stole valuable IP. In 2023, China banned Micron in critical infrastructure. Last week, Micron completely exited China's AI data centre market.

The other part of the Micron story that remains relevant is Simplot's wild business pivot.

One quote summarizes it perfectly. During the release of Windows 95, someone asked Simplot about using computers. Simplot never owned a PC and hammered home the point: "Hell, boy, I came before the goddamn typewriter."

With or without a PC, Simplot's knowledge of potato economics proved extremely valuable for Micron.

The current AI boom is so all-encompassing that we're seeing different industry experiences driving everything forward. Elon's career in energy innovation and manufacturing was pivotal in xAI building a $6B AI data centre in 122 days (typically takes 2-3 years). Sam Altman's previous career running Y-Combinator made him one of the world's foremost dealmakers and capital allocators—handy since OpenAI needs to financially engineer $1T in capex spend.

In 50 years, we'll look back at this period and find stories of people in wildly different industries applying random domain-specific knowledge that unlocked AI in a new way…although it's unlikely any of them would have started their careers by boiling wild horse meat and potato scraps.

Stay curious 🙂

- John.